JEPPE UGELVIG: WHICH DEFINITION OF FASHION IN ART IS USEFUL? AND VICE VERSA?

Dobrila Denegri: I would like to talk about your curatorial work, since your contribution to the conference was entitled “Curating Fashion Production” First of all, would you consider yourself a fashion curator?

Jeppe Ugelvig: I am primarily an art historian interested in fashion. I don't have the merit to be called a fashion curator, nor am I a historian of fashion exhibitions. Still, I'm interested in fashion and fashion production, and my art historical work broadly concerns itself with histories of consumerism and how it relates to art history. So, there's no better object than the intersection of art and fashion, which has become my focus in recent years.

DD: Still, you are curating exhibitions, in addition to your work as a writer and editor. How did it all begin? What triggered your interest in more critical and “expanded” forms of fashion production?

JU: One can only understand one's work as a reaction to what's already out there, as well as what feels like it isn’t there. I felt a certain dissatisfaction with contemporary systems of cultural mediation. I entered this field because I aspired to be a fashion editor. That was my childhood dream. As I enrolled at Central Saint Martins at 18, my dream of a kind of smart, intellectual journalistic practice within commercial fashion publishing withered as doomsday narratives surrounding fashion media grew in force.

Additionally, I felt dissatisfied with the critical vocabulary used in the fashion industry. I drifted into art criticism and curation, eventually landing at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard. Upon arrival, I thought I would pack up my fashion stuff and leave it behind. If anything, CCS Bard is an ivory tower of post-1960s conceptual practice between New York and Western Germany; indeed, not a space for frivolous fashion. But I was truly wrong. In the end, that became the place where I could explore fashion from a perspective that Elizabeth Wilson indicates when she talks about it as the threshold between art and non-art, aesthetics and industry, autonomy and utility. Fashion is weird and complicated because it's a branch of aesthetics and a mass pastime. It's a regime of images. It's an industrial production system.

Additionally, we can consider many other aspects, such as social technologies of the self or a way of collective identification.

This is a hugely problematic field, and, of course, it doesn't make curating any easier when we consider curating fashion in its full phenomenological extent.

DD: Fashion exhibition-making is still relatively static, isn’t it? How do you see it, in the past and now?

JU: As I understand it, one lineage is the art historical approach to the object and its preservation in the museum. An object becomes emblematic of the history of costume, anthropology, or sociology. An object, such as a garment, is considered meaningful as a representative artefact of a particular period, defined by sociologies of styles and production technologies.

The other modality is post-Diana Vreeland. As far as I know, she was the first to curate an exhibition with a living designer. Today, there are spectacular itinerant blockbuster exhibitions that function as a hagiography of a designer or a brand. The emphasis lies on the identity of the designer as a genius. The designer's work is treated as a cohesive oeuvre, on par with that of an artist, and similarly revered. Once, the couturier was an artist, and now the creative director is an artist—it is an ubiquitous comparison. So, it is not so different from art. Art is still hopelessly obsessed with its authors, and one can only understand artworks through the authorship of their makers.

DD: How do you see the role of fashion studies and fashion theory in the context of exhibition-making? Where do your interests lie?

JU: Fashion studies emerged in the interdisciplinary and postmodern 80s, where a range of “-studies” disciplines emerged. And this is the strength and the weakness of fashion theory as we call it today. When you read fashion theory, there is a sense that fashion is incredibly broad and omnipresent in our lives; it is closer to a symptom of an ontology. However, I would also argue that fashion theory has a significant issue: it is an intensely gate-kept and unmediated space, and many of us, myself included, are aware that there are seemingly parallel conversations happening within Academia, within the curatorial and within the editorial that have absolutely no connection between them.

Personally, I developed an interest in the relationship between art and fashion. I encountered a desire to take art stuff into fashion, but I also identified fashion things in art and got excited about these small discoveries here and there. I also found there to be use and abuse of each other in very superficial, formal ways. So when I started digging into this more theoretically, I realised the relationship between the two systems was an intensely under-theorised space. It is also a cause for frequent demonisation of fashion through the prism of art, because fashion is often seen as an evil force of capitalism, while art is not. This has never led very far in terms of artist engagement. I very much agree with Nancy Troy, who, in her book, “Couture Culture”, observed how art historians have been looking at artist engagement with fashion, and settled for a very narrow comparison of the two fields. One that focuses on formal similarities that are often visually powerful but generally lack substance. So, if it appears to be fashion, we'll treat it as such and disregard the various conditions of production, institutional reception, and economic exchange that surround different cultural practices and objects. We often blend wearable art with ready-made sartorial objects and artists who engage with fashion topics such as style, identity, and representation. All of these ventures are, of course, completely valid. However, pinning them together under the umbrella term of “fashion” has become increasingly problematic because concepts such as clothing, style, self-adornment, merchandise, costume, performance, and craft are all concepts that require their definitions and their histories. They have their histories and analytical parameters.

DD: How do you approach this con/fusion of terms, fashion and art?

JU: At the beginning of my MA degreeI asked myself: “Which definition of fashion in art is useful? And vice versa?”, and I haven't stopped asking this question till today. Rather than reducing it to a question of ontology or form, what has become important to me is looking at their production systems and bringing them back to material systems.

I owe a great deal to Philipp Ekardt and his concept of aesthetic praxeology, which examines how a cultural object, image, or practice operates within a cultural context. In other words, rather than saying, 'Oh, it's a dress; it must be fashion,’ We should understand: does this dress go into magazines? If so, which ones? Is it bought or is it sold in galleries or a shop? These are fundamental things that most of us would have the answer to. That's a broadly understood approach to this topic that I find useful.

DD: Talking about the hybridity between art and fashion, you have published an article in Frieze about the intersection of luxury, culture and marketing through brand-owned museums. What is this intersection about?

JU: It has nothing to do with the cultural practices of people like us. It has nothing to do with artists and has very little to do with fashion designers. It's about fashion money, and where the fashion money is going. These material or materialist questions about production and capital very quickly point to the institution as an incredibly desirable commodity form. Any conversation about how art and fashion are presented in institutional or economic contexts should bear in mind their most political aspects, specifically the uses and abuses of these forms that we often think of as pure, such as a museum. My summary of myself is: looking at the fashion from the perspective of political economy, and also one that works against this totalising paradigm of criticality.

DD: Let’s talk more about fashion and criticality... what does it mean for you?

JU: Criticality has a very particular history of art and aesthetics; it's essentially an idea of autonomy - autonomy from systems of production, from systems of commodification, from quotation in various ways in consumer capitalism. Fashion is never going to fit into that paradigm -and thank God it doesn’t- because I do think the most important and most interesting thing about fashion is its embodied state of commodification. Fashion is a testament to the living commodification of life, and what one does to live in it is how one negotiates a commodified life and a commodified body; that's what makes fashion so incredibly interesting and relevant as an objective study.

DD: And then there are the other types of fashion practice, those that don’t fit in the scenarios you just mentioned...

JU: Yes, the expanded, critical, hybrid, fringe, and independent practices. I am invested and interested in bringing them forward. I'm interested in these practices because they're essential to the production of fashion, even in those mainstream ways. Often, these fringe practices, as they attempt to make a living on the fringes, end up prototyping forms of fashion entrepreneurship that become mainstream or are adopted by mainstream fashion businesses. And finally, rather than a critical practice, what I've increasingly drawn to is a concept of a cultural materialist practice, a term informed by an art historian, Craig Owens, who wrote for the October journal. In his insightful summary of the tradition of institutional critique from the 1970s and 1980s, he ultimately asks what comes after. The artists who investigated their institutional frame at the end of the 1970s claimed that self-investigation and self-reflexivity were, to some extent, over. Owens pushes back and suggests that the postmodern displacement from work to frame lays the groundwork for a materialist cultural practice. To say it in his own words from 1992: “I want to suggest that the postmodern displacement from work to frame lays the groundwork for a materialist cultural practice—one which, to borrow Lucio Colletti’s definition of materialist political practice, “subverts and subordinates to itself the conditions from which it stems.”

DD: Talking about ideas that influenced you, I’d like to get back to your formative path, once you have ‘given up on your dreams of being a fashion journalist’...

JU: Back then, I was intensely following practices like those of Matthew Linde's. Matthew opened his show in 2017, and I recall attending it. Additionally, I conducted archival work at Bard about Susan Cianciolo, DIS, Bless, alongside a range of other practices that blended the registers of art and fashion. I became increasingly interested in the ways they were working with fashion in the 1990s. It was a time of deep recession, art was in a relatively commercial moment, and fashion was considered the last creative currency on guard. And against the backdrop of the early 1990s recession, downtown New York was a hub for organised cultural activity that was mainly intended for showing off to friends or impressing fellow community members who were doing the same things. It was in this environment that the Bernadette Corporation organised itself. They were a community of young creatives that came together to organise parties at the Terry Mugler Room at the Club USA, which was just off Times Square, in a room next to Michael Alig's Club Kid parties. They assumed the form of a corporation, which to them was the perfect alibi for not having to have a fixed identity. They did a variety of things, including fashion performances, which they described as “the simultaneous practice of fashion and fascism, involving group-coordinated dress-ups.”They did fashion bazaars on parking lots and various other things until they finally relaunched in 1995 as a fashion brand.

DD: What did you like about Bernadette Corporation?

JU: They started by mocking a fashion project, but they ended up doing fashion that became very prototypical of what was to come, as well as the post-industrial fluidity working across media systems, which today has become so commonplace. I would say they changed fashion, showing what's to come.

DD: At around the same time, Susan Cianciolo also appeared, right?

JU: Yes, she emerged at a very similar time, and was an early collaborator of Bernadette Corporation, and Bernadette herself helped Susan style her first collection. Susan was someone who hacked her way into the art system, or an artist who hacked her way into the fashion system. These are all very porous boundaries, but she certainly made use of art in launching RUN, a very unusual brand that employed a crafty, ragtag aesthetic. She often made her clothes, organising knitting circles with her friends, who were usually artists. Still, she became so successful, even commercially, that she was sought after by Bergdorf Goodman and many other places, and experienced a kind of success that forced her to formalise her business more and more. She maintained this connection to art and used it as a space for promotion.

DD: Recently, here in MACRO, the most unusual retrospective of Bless, another collective you studied, was organised. It was a library of all catalogues, magazines, and publications featuring their 25-year-long career, which was practically blocking the entrance to the almost empty exhibition room... I really liked it!

JU: Bless! I really love them because they are fiercely committed to the product form. They're not interested in art; they're not interested in the autonomous artwork. They're interested in things that are part of everyday life, which have a use value that can still be conceptually engaging.

DD: All these creatives you mentioned belonged to the same period, more or less, but you also connected their work with the work of some younger generations, right?

JU: I didn't want to make this study a total nostalgic '90s moment. All of these people were friends, and it was a very thick air to cut through as a 22-year-old MA student. So, I looked into DIS because they incorporated many of these legacies or models of working into the digital 2000s. DIS emerged as a collective after the financial crisis. They were either art students, art graduates, or fashion graduates who saw fashion work drying up in front of them. What they did was to start a blog, as everyone was doing in 2008. They utilised all their fashion and art skills and put it online for free as part of this post-internet generation that they had very much platformed..

DD: This research at Bard ultimately evolved into an exhibition...

JU: Yes, I found a way to do mini retrospectives. It was a delightful and wonderful exhibition with a wide variety of fun archival objects. But of course, so much did not make it into the show; so many images or other paraphernalia. But since I'm always a writer before I'm a curator, and writing is my safe space, I turned all this material and research into a book, “Fashion Work”, launched in 2020, seven days before COVID.

DD: With this book, you raised so many questions about the specificity of fashion as an object, and how one deals with it in the art and exhibition context. What did this research lead you to in terms of your following projects?

JU: The Next exhibition I did was almost a total opposite to “Fashion Work”. I was asking: ‘What does it mean when garments make an appearance in the museum? What information is stored in them, and what levels of obscurity exist there?’ I took the title “Sartor Resartus” from the wonderful book by Thomas Carlyle about a fictional philosopher, Diogenes Teufelsdröckh, and his thesis “Clothes: Their Origin and Influence.” Teufelsdröckh’s groundbreaking project ultimately fails and remains unfinished. However, Carlyle can still be credited for having accidentally invented the concept of fashion semiotics: the reading of clothes as symbols of meaning. As the book makes clear, the deciphering of fashion’s signifiers is a near-impossible task, as they exist in a constant state of flux between personal, material, political, historical, and cultural signification. There are these lovely passages in the book where he's sitting on the street, observing people passing by, trying to get to the core of who they are and what information is being communicated through them. He's left with very little. It remains a complete mystery. Contrary to what I pointed out, the failure of fashion synonyms will not really take us to many places, because fashion science is always in flux, and fashion is an inherently complex medium with many layers of information on top of it.

DD: Who were the artists or designers you were involved with, and how would you describe the exhibition?

JU: Pia Camil, Bruno Zhu, Anna-Sophie Berger, Nina Beier, Anna Franceschini, Tenant of Culture, among others. The exhibition aimed to explore clothes as a signifier at once empty and overburdened: as expressions of people and places, as palimpsests for capitalist production cycles, and as nondescript material debris. The exhibition, void of living bodies, presents a series of “clothing objects” made or found by artists, presented as sculpture, costume, painting, and moving image, haunted by various forms of signification. What knowledge, the exhibition asks, can we gather from studying clothes when they are severed from everyday life? Can wearability and value be used as a classifying device? And to what extent is “fashion" ever successfully signified by things? The artists in the exhibition offer no easy solution to this question, but instead a wealth of complex, confusing, and humorous narratives through their work. Pia Camil’s piece was about the fashion supply chain, which is something that has come to preoccupy me a lot recently. Bruno Zhu’s pants, which are becoming gloves, were raising questions about what happens to clothes in the hands of an artist who is also trained as a fashion designer. Nina Beier works a lot with, I would say, the biographies of things and the social life of objects.

It's essential to note that these exhibitions were often extended into the realm of publishing and editing. I am very committed to editorial format as a form of curating. I view exhibitions as an editorial space, and I'm often more excited about publishing than I am about exhibition-making, primarily due to logistical reasons. The shows are costly to make, and you're constantly faced with limitations, whereas it's easier sometimes to manage and put it in a magazine. These magazines have become a kind of platform for readers of the exhibitions I curate. An exhibition is also an opportunity to invite the artist into an editorial space as writers or image speakers, but also to ask 15-20 writers to illuminate this theme.

DD: Can you tell me more about the project “The Endless Garment”?

JU: In 2021, I was invited to work on a project at X Museum in Beijing, which drew on the prolonged periods I had spent in Hong Kong. I was interested in how, in thinking about fashion and fashion production, the space that China occupies in our imagination, both as a sort of Orientalist, stylistic origin from where we can appropriate images and aesthetics in the West, but also as a site of production in the kind of global 20th century where made-in-China has become.

DD: What was a challenge for you in working in China or with Chinese artists/designers?

JU: I was interested in how this was unfolding, especially while living in New York, where I’ve been observing a very prolific discourse about Asian American diasporic identity. And how these questions would be looped through the idiom of fashion and style. Fashion became a place where one could, in a bricolage style, put together and reassemble one's identity within the material system of migration. So it was a kind of experiment, like what happens when you take this discourse of diaspora “back home,” to Asia, in a way. It was a hyper-material, hyper-materialist look at fashion as a supply chain full of lived lives within it—a supply chain where lots of subjectivity is constantly produced and reproduced.

DD: How did you approach these issues curatorially?

JU: Being an art/fashion curator, you have the idea of inviting fashion designers to create an art project. Over time, we've come to learn to respect a fashion practice and understand its essence, especially in a curatorial sense, which often involves a mannequin or, at the very least, a garment that serves as a display structure for the fashion.

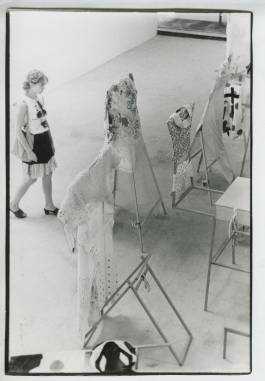

Preparing for the Bernadette Corporation S/S ’96 fashion show.

Photography Cris Moor

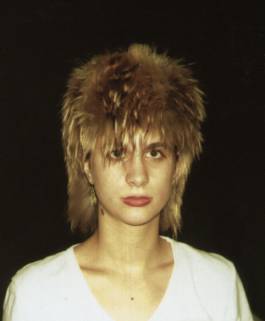

Bernadette Corporation S/S ’96 fashion show backstage.

Photography Eline Mugaas

Bernadette Corporation S/S ’96 fashion show, backstage.

Photography Cris Moor

Bernadette Corporation F/W ’95 fashion show.

Photography Cris Moor

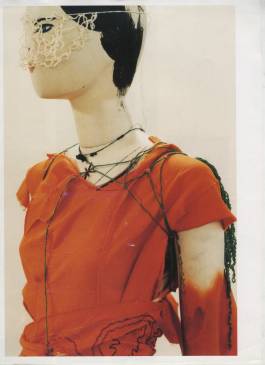

Run performance.

Courtesy of Susan Cianciolo and Bridget Donahue, NYC

Run 3, “Pro-Abortion Anti-Pink”.

Photography Cris Moor

“Run 7”.

Photography Rosalie Knox. Courtesy of Susan Cianciolo and Bridget Donahue, NYC

“Run 9” presentation, Alleged Galleries, 1999. Photography Ivory Serra.

Courtesy of Susan Cianciolo and Bridget Donahue, NYC

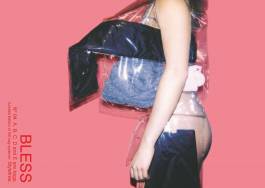

“N°00 Furwig” advertising, 1996.

Courtesy BLESS

“N°04 Bags”, 1998.

Courtesy BLESS

“N°13 Basics” show, 2001.

Courtesy BLESS

“N°54 Remembrance Subito” presentation, 2015.

Courtesy BLESS

“Hoop Dreams”.

Courtesy DIS

“Highly Effective People”, 2009.

Courtesy DIS

“Younger than Rihanna,” 2013.

Courtesy DIS

DIS, “Watermarked”, 2012. 2 min.

Courtesy DIS

INSTAGRAM

@EXPERIMENTS.FASHION.ART