studio Stefania Miscetti, Marina Abramović, Performing Body

1997

MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ: I AM INTERESTED IN THE SITUATION OF TRANSITORINESS AND ABANDONMENT, BEING OPEN TO EVERYTHING THE WORLD HAS TO OFFER

Art's auto-referentiality is possible only in decadent societies and can exist only in towns. As soon as a person finds him/herself outside the town, in a desert, the “object” no longer has its function, and art for art's sake loses its meaning. Initially, art did not have references to its own context but was created out of interest in a human being, and the human need for religion and ritual rites.

Marina Abramović

Understanding Marina Abramović's art cannot be separated from reflections on her personality and attitudes toward the manner of life and the creation of an artist within a specific reality. In the quotation above, the artist precisely defines the sphere of reference for her work, thereby confirming Wittgenstein's thesis on the identification of ethics and aesthetics, the arts and life.

Historically, this conception of art is rooted in avant-garde or neo-avant-garde movements of the century, which have fundamentally altered the categories of understanding and perception of artistic work. Following the trail first blazed by Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, the artists of the ‘50s and ‘60s experimented with new ways of expression that brought to the fore an interest in the body, movement, and space, insisting on the demystification of the artistic act, the democratisation of art, and the involvement of the spectator. These tendencies obviously question the material status of the artistic object, making way for new forms of artistic practice - characterised by modern criticism as post-object (Donald Kersham) or dematerialisation of the object (Lucy Lippard, John Chandler) - which emphasise the attitude and behaviour of artists in concrete, processual operations.

The following conversation took place on the occasion of the opening of Marina Abramović's first solo exhibition in Rome, at the gallery Stefania Miscetti, during which she spoke about the key aspects and development stages of her work from the beginning to the present day.

Dobrila Denegri: You started to realise the first audio environments in the early ‘70s in Belgrade, and then you turned towards direct work with the body. What did the experience of the performance mean for you?

Marina Abramović: Yes, initially, I did audio installations, which, in time, revealed a growing need for the involvement of the body, but exclusively via sound, which was the basic element. Thus, I can say that I entered the art of performance through the sound, and my first performances were highly rhythmical, as revealed by fair very names: “Rhythm 02”, “Rhythm 2”, “Rhythm 4”. This shift to body art happened spontaneously, almost unconsciously, and after the first performance, I simply could not imagine working in any other medium.

Through the performance, I recognised the possibility of establishing an energy dialogue with the public, which is conducive to energy transformation. I could not perform a single work without the presence of an audience, because it gives me the energy that I, through a specific action, assimilate and send back, creating a kind of energy field. In all my performances, I examined the physical and mental limits I could push beyond, drawing on the energy I drew from the audience.

DD: Your work always revealed an intention of bringing the body into extreme states, which is close to certain ritual rites practised in ancient cultures you have studied or came in direct contact with while travelling, already during the period of cooperation with Ulay.

MA: Yes, when I went to Tibet, or to live among the Aborigines in Australia, or when I learned of some Sufi rituals, I understood that these cultures have a long tradition of meditative techniques which bring the body into the a borderline state which enables a mental leap ushering us into a different dimension of existence and eliminating fear from pain, death or bodily limitation. None in Western civilisation are so frightened and, by contrast to Eastern cultures, have never developed the techniques which could shift bodily limits. For me, the performance was a form which enabled me to make this mental leap. Initially, while I worked alone or in the first stage of my work with Ulay, there was an element of danger. Confrontation with physical pain and the body's exhaustion was highly important, as these are states of total “presence” in one's own body, states that make a person awake and conscious. In the early '80s, when the artistic scene began to change, and all artists turned to painting, Ulay and I decided to turn to nature, to go to the desert and see what this miniature landscape had to offer. We also wanted to learn about the heritage of ancient cultures by integrating with them and then transforming that experience into our work, thus forming a bridge between East and West. “Night Sea Crossing” is a performance that emerged from this concept and consisted of seven hours of nonstop sitting, requiring maximum mental concentration and physical control.

DD: Tell me something about the idea of travelling and the role it has in your work and understanding of the arts in general.

MA: When I left Yugoslavia, I decided to be a modern nomad. I see the whole world as my studio, and I am increasingly interested in being in the “place” which I call “the space in between”, thus to be in a span between two places, when you leave one and arrive in another (like waiting rooms, central stations, etc.). I am interested in this kind of situation of space- and time-wise transitoriness and abandonment, open to everything the world has to offer. For me, this is a specific creative state I wish to be in. My entire work, from the very beginning, reveals the idea of crossing the borders in both physical and metaphorical senses. Western civilisation has completely lost contact with nature, and through my work, the manner in which I use specific material (crystal, copper, human hair...) I wish to indicate the need to reconnect the human with the "planetary" body.

DD: While realising “Transitory Objects”, you have developed your own system of classification of minerals whereby light-coloured quartz corresponds to the eyes of the planet, green to its hands, opaque to the mind, and rose to the heart of the planet.

Sodalite is the spirit, amethyst the wisdom tooth, fuchsite the stomach. What is the function of “Transitory Objects”, and how do they fit into your previous work?

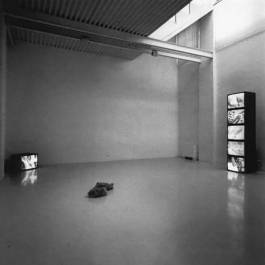

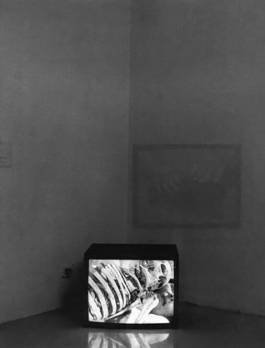

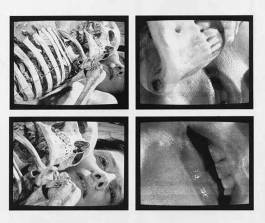

MA: Many people think that by working on the “Transitory Objects”, I have left the performance. For me, the “Transitory Objects” signify an even greater penetration into performance, but this time the objects are done for the audience, and they become a work of art for me only when someone uses them. In traditional performances, spectators always play a passive role as observers, but I wish everyone could have their own experience. I think that the individual, physical experience is extremely important, since this is the only way to change our awareness of things. No one has even changed by watching a performance or reading a good book, but a real experience may change one's consciousness. I do not believe that art can change the world, but I do think that certain artistic actions may influence a change of mind. I also wish to confront the people directly with all the aspects which are suppressed in our culture the most, because these are related to primary fears: fear of death, pain. This is the underlying idea of the video installation “Cleaning the Mirror No 1”, where I clean a human skeleton, implying that a skeleton is our last mirror. I also deal with the theme of confronting death and bodily transitoriness in another assemblage called “Cleaning the Mirror No 2”, where I lie prone with a skeleton over my body, my breathing moving it, alluding precisely to the flimsy limit between life and death. The third part of the work, “Cleaning the Mirror”, is a reconstruction of spiritual power in the body through the use of objects that emit a special kind of energy.

DD: During the ‘60s and the ‘70s, the interest of the artists was directed towards the real experience of time and space, and the artists who engaged in performance art considered theatralization the most negative of all aspects. You perform your latest meta-performances “Biography” and “Delusional” in the theatre where you act or re-act the actions you had in the 70s. What is the meaning of the need to repeat specific actions in a different context, and how do you understand the idea of the originality of performance?

MA: I feel the need to repeat certain acts. I remember being surprised when I saw Kounellis repeat his installation with the horses, initially performed in Sargentini's gallery, at the Venice Biennale years later. Interestingly, the meanings of certain concepts change over time, and I am interested in that aspect of change. In addition, a few people have seen the original performances we did in the ‘70s, and the documentation is inadequate, so that this period is now being mystified.

On the one hand, my work has always been dominated by biographical elements. At this stage of life, I need to return to my roots and reexamine aspects of my individual and cultural heritage. On the other hand, I feel the need to replay not only my performances, but also those of other artists who worked in the same manner (Gina Pane, Vito Acconci, Chris Burden), because if I can do what they did, so can anyone else. Thus, the audience today can perform the same actions and personally undergo the experience. With this in mind, I wish to change the idea of originality, which has generally been linked to this type of work.

DD: Tell me something about the elements of baroque, glamour, irony, and humour, which are all present in your new performances and represent a complete novelty compared with the previous stages of your work.

MA: My latest monumental project, done by myself and Ulay, was walking the Great Wall, and this long performance was a very deep and intensive experience for both of us.

For Ulay, it represented the search for identity and for me, the test of my physical and mental capacities. I have discovered aspects of my personality I have not expressed before, as I wished to create a certain image of myself in the public eye and, in line with that, manifested only my radical side, or rather a kind of strong, masculine energy, in my earlier performances. I have always had an open concept of life, and to fully realise myself, I wanted to introduce other aspects of my personality into my work, such as glamour, kitsch, humour, or irony. I primarily wanted to work on all the things that cause shame.

I could account for this change in my work by pointing to the difference between Zen Buddhism in the Japanese tradition and Tibetan Buddhism. In Zen Buddhism, the clearing of consciousness is accomplished through concentration and looking at a white wall.

Tibetan Buddhism does not require that; it is full of images and notions, much more baroque and human. It is precisely this baroqueness, as the affluence of contradictory and opposite states and images, that I wish to examine in my work. For this kind of performance, I prefer the theatre since this context allows me to position myself as a kind of a mirror upon which the audience may project its own internal conflicts and controversies. This is also what I intend to do in my future work.

DD: What is the meaning of “Balkan Baroque” for you?

MA: For me, the “Balkan Baroque” is a special metaphor which has nothing to do with the possible meaning of the word in the historical-artistic sense, and represents a baroqueness of mind, or rather a kind of irrationality, a madness typical of a specific geographic area. The environment, and in the first place, the geographic configuration, is extremely important for the formation of a collective psychology. The Balkans is a place where East and West meet, thus a place where two contrary civilisations come in contact and mix, causing all this contradictoriness in our nature, which no one can understand and which I call the baroqueness of mind. This is like a permanent intertwining of strong emotions, love, passion, tenderness, hatred, fear, sex and shame. The Balkans is a bridge between East and West, and this bridge is constantly swept by winds, which is why its history is so stormy. I do not think that my work can offer any answers, nor is there a rational interpretation or solution to the contradictoriness we refer to.

DD: The process of physical and mental preparation for the performance or a work of art has an important role in your work, and you call it "house cleaning". Can you tell us more about this analogy and understanding of the body as a house and, in general, about the practice of body “preparation”?

MA: From the mid-nineties, I have started workshops developing the idea of body preparation, alone and with my students. These workshops implied staying in a completely isolated place, as well as a special regime of life and mental and physical activities (seven days without communications, food, early morning rises, meditative exercises, etc.). After that, each of us would perform a task using only our own bodies. The term “house cleaning” is of recent origin because I really understand my body as a house, as do other artists - according to what they show in their works (e.g. Louise Bourgeois) - or other cultures (e.g. Muslim drawings). I think that what we should do now is clean the house. This house cleaning actually brings the body into a state that makes it especially receptive to a specific energy, and this state of “clear mind” makes it possible to create a work that will be sufficiently strong to transform others. If the artist does not have a clear mental picture, his/her work will express that state of disorder and inarticulateness. In the modern world, so deeply in crisis due to hyperproduction, art is not needed, as it only deepens the crisis and pollution. Art should be the oxygen of society.

“House cleanings” are the workshops I do with my students, but they are also my own performances. It is important, however, that body preparation is not practised only during specific periods but becomes a principle of life. I was influenced by a text of Cennino Cennini who writes how an artist should prepare himself to create a work of art when he is given an order from the pope or the king: he should stop eating meat three months before, drinking wine three months before, stop having sexual intercourse a month before, and three weeks before he should put a plaster on his right hand and then, when he is supposed to start painting, he will break the plaster and be able to draw a perfect circle. My concept of “Cleaning the House” follows in this tradition.

At the moment when all philosophical systems are brought into question, when the religious ones have lost their absoluteness, and the systems of values have disappeared, while the new ones are yet to come, the question of the role of the arts arises, along with the task of the artist.

Marina believes that an artist can be a companion who accompanies a person on a journey to discover his/her inner being. She creates art that goes beyond the level of visual perception and precisely opens new channels for awareness. In this sense, her work is interactive in a specific way, positioning the observer as the activating factor.

Interactivity becomes an increasingly dominant characteristic of modern art, regardless of the material the work is made of, since it corresponds to the principles of contemporary information systems, which fully shape our consciousness and behaviour.

Modern society is characterised by a frenetic need to overcome one's own limits of the body and consciousness, for the alternation of perception and communication, which are possible to realise through instant means of techno-culture.

In this context, the work of Marina Abramović is significant, as it does not express the romantic, utopian conviction that art can change the world, but rather instigates the real possibility of opening the channels of individual awareness of the world and its beings.

The interview is published in the catalogue of the exhibition “Performing Body”, edited by Charta, Milan.

1997

MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ: I AM INTERESTED IN THE SITUATION OF TRANSITORINESS AND ABANDONMENT, BEING OPEN TO EVERYTHING THE WORLD HAS TO OFFER

Art's auto-referentiality is possible only in decadent societies and can exist only in towns. As soon as a person finds him/herself outside the town, in a desert, the “object” no longer has its function, and art for art's sake loses its meaning. Initially, art did not have references to its own context but was created out of interest in a human being, and the human need for religion and ritual rites.

Marina Abramović

Understanding Marina Abramović's art cannot be separated from reflections on her personality and attitudes toward the manner of life and the creation of an artist within a specific reality. In the quotation above, the artist precisely defines the sphere of reference for her work, thereby confirming Wittgenstein's thesis on the identification of ethics and aesthetics, the arts and life.

Historically, this conception of art is rooted in avant-garde or neo-avant-garde movements of the century, which have fundamentally altered the categories of understanding and perception of artistic work. Following the trail first blazed by Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, the artists of the ‘50s and ‘60s experimented with new ways of expression that brought to the fore an interest in the body, movement, and space, insisting on the demystification of the artistic act, the democratisation of art, and the involvement of the spectator. These tendencies obviously question the material status of the artistic object, making way for new forms of artistic practice - characterised by modern criticism as post-object (Donald Kersham) or dematerialisation of the object (Lucy Lippard, John Chandler) - which emphasise the attitude and behaviour of artists in concrete, processual operations.

The following conversation took place on the occasion of the opening of Marina Abramović's first solo exhibition in Rome, at the gallery Stefania Miscetti, during which she spoke about the key aspects and development stages of her work from the beginning to the present day.

Dobrila Denegri: You started to realise the first audio environments in the early ‘70s in Belgrade, and then you turned towards direct work with the body. What did the experience of the performance mean for you?

Marina Abramović: Yes, initially, I did audio installations, which, in time, revealed a growing need for the involvement of the body, but exclusively via sound, which was the basic element. Thus, I can say that I entered the art of performance through the sound, and my first performances were highly rhythmical, as revealed by fair very names: “Rhythm 02”, “Rhythm 2”, “Rhythm 4”. This shift to body art happened spontaneously, almost unconsciously, and after the first performance, I simply could not imagine working in any other medium.

Through the performance, I recognised the possibility of establishing an energy dialogue with the public, which is conducive to energy transformation. I could not perform a single work without the presence of an audience, because it gives me the energy that I, through a specific action, assimilate and send back, creating a kind of energy field. In all my performances, I examined the physical and mental limits I could push beyond, drawing on the energy I drew from the audience.

DD: Your work always revealed an intention of bringing the body into extreme states, which is close to certain ritual rites practised in ancient cultures you have studied or came in direct contact with while travelling, already during the period of cooperation with Ulay.

MA: Yes, when I went to Tibet, or to live among the Aborigines in Australia, or when I learned of some Sufi rituals, I understood that these cultures have a long tradition of meditative techniques which bring the body into the a borderline state which enables a mental leap ushering us into a different dimension of existence and eliminating fear from pain, death or bodily limitation. None in Western civilisation are so frightened and, by contrast to Eastern cultures, have never developed the techniques which could shift bodily limits. For me, the performance was a form which enabled me to make this mental leap. Initially, while I worked alone or in the first stage of my work with Ulay, there was an element of danger. Confrontation with physical pain and the body's exhaustion was highly important, as these are states of total “presence” in one's own body, states that make a person awake and conscious. In the early '80s, when the artistic scene began to change, and all artists turned to painting, Ulay and I decided to turn to nature, to go to the desert and see what this miniature landscape had to offer. We also wanted to learn about the heritage of ancient cultures by integrating with them and then transforming that experience into our work, thus forming a bridge between East and West. “Night Sea Crossing” is a performance that emerged from this concept and consisted of seven hours of nonstop sitting, requiring maximum mental concentration and physical control.

DD: Tell me something about the idea of travelling and the role it has in your work and understanding of the arts in general.

MA: When I left Yugoslavia, I decided to be a modern nomad. I see the whole world as my studio, and I am increasingly interested in being in the “place” which I call “the space in between”, thus to be in a span between two places, when you leave one and arrive in another (like waiting rooms, central stations, etc.). I am interested in this kind of situation of space- and time-wise transitoriness and abandonment, open to everything the world has to offer. For me, this is a specific creative state I wish to be in. My entire work, from the very beginning, reveals the idea of crossing the borders in both physical and metaphorical senses. Western civilisation has completely lost contact with nature, and through my work, the manner in which I use specific material (crystal, copper, human hair...) I wish to indicate the need to reconnect the human with the "planetary" body.

DD: While realising “Transitory Objects”, you have developed your own system of classification of minerals whereby light-coloured quartz corresponds to the eyes of the planet, green to its hands, opaque to the mind, and rose to the heart of the planet.

Sodalite is the spirit, amethyst the wisdom tooth, fuchsite the stomach. What is the function of “Transitory Objects”, and how do they fit into your previous work?

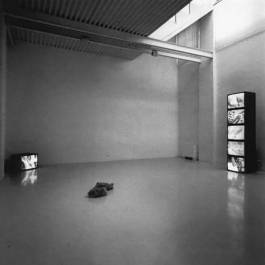

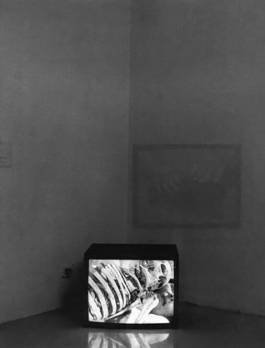

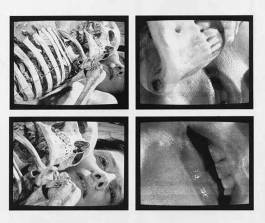

MA: Many people think that by working on the “Transitory Objects”, I have left the performance. For me, the “Transitory Objects” signify an even greater penetration into performance, but this time the objects are done for the audience, and they become a work of art for me only when someone uses them. In traditional performances, spectators always play a passive role as observers, but I wish everyone could have their own experience. I think that the individual, physical experience is extremely important, since this is the only way to change our awareness of things. No one has even changed by watching a performance or reading a good book, but a real experience may change one's consciousness. I do not believe that art can change the world, but I do think that certain artistic actions may influence a change of mind. I also wish to confront the people directly with all the aspects which are suppressed in our culture the most, because these are related to primary fears: fear of death, pain. This is the underlying idea of the video installation “Cleaning the Mirror No 1”, where I clean a human skeleton, implying that a skeleton is our last mirror. I also deal with the theme of confronting death and bodily transitoriness in another assemblage called “Cleaning the Mirror No 2”, where I lie prone with a skeleton over my body, my breathing moving it, alluding precisely to the flimsy limit between life and death. The third part of the work, “Cleaning the Mirror”, is a reconstruction of spiritual power in the body through the use of objects that emit a special kind of energy.

DD: During the ‘60s and the ‘70s, the interest of the artists was directed towards the real experience of time and space, and the artists who engaged in performance art considered theatralization the most negative of all aspects. You perform your latest meta-performances “Biography” and “Delusional” in the theatre where you act or re-act the actions you had in the 70s. What is the meaning of the need to repeat specific actions in a different context, and how do you understand the idea of the originality of performance?

MA: I feel the need to repeat certain acts. I remember being surprised when I saw Kounellis repeat his installation with the horses, initially performed in Sargentini's gallery, at the Venice Biennale years later. Interestingly, the meanings of certain concepts change over time, and I am interested in that aspect of change. In addition, a few people have seen the original performances we did in the ‘70s, and the documentation is inadequate, so that this period is now being mystified.

On the one hand, my work has always been dominated by biographical elements. At this stage of life, I need to return to my roots and reexamine aspects of my individual and cultural heritage. On the other hand, I feel the need to replay not only my performances, but also those of other artists who worked in the same manner (Gina Pane, Vito Acconci, Chris Burden), because if I can do what they did, so can anyone else. Thus, the audience today can perform the same actions and personally undergo the experience. With this in mind, I wish to change the idea of originality, which has generally been linked to this type of work.

DD: Tell me something about the elements of baroque, glamour, irony, and humour, which are all present in your new performances and represent a complete novelty compared with the previous stages of your work.

MA: My latest monumental project, done by myself and Ulay, was walking the Great Wall, and this long performance was a very deep and intensive experience for both of us.

For Ulay, it represented the search for identity and for me, the test of my physical and mental capacities. I have discovered aspects of my personality I have not expressed before, as I wished to create a certain image of myself in the public eye and, in line with that, manifested only my radical side, or rather a kind of strong, masculine energy, in my earlier performances. I have always had an open concept of life, and to fully realise myself, I wanted to introduce other aspects of my personality into my work, such as glamour, kitsch, humour, or irony. I primarily wanted to work on all the things that cause shame.

I could account for this change in my work by pointing to the difference between Zen Buddhism in the Japanese tradition and Tibetan Buddhism. In Zen Buddhism, the clearing of consciousness is accomplished through concentration and looking at a white wall.

Tibetan Buddhism does not require that; it is full of images and notions, much more baroque and human. It is precisely this baroqueness, as the affluence of contradictory and opposite states and images, that I wish to examine in my work. For this kind of performance, I prefer the theatre since this context allows me to position myself as a kind of a mirror upon which the audience may project its own internal conflicts and controversies. This is also what I intend to do in my future work.

DD: What is the meaning of “Balkan Baroque” for you?

MA: For me, the “Balkan Baroque” is a special metaphor which has nothing to do with the possible meaning of the word in the historical-artistic sense, and represents a baroqueness of mind, or rather a kind of irrationality, a madness typical of a specific geographic area. The environment, and in the first place, the geographic configuration, is extremely important for the formation of a collective psychology. The Balkans is a place where East and West meet, thus a place where two contrary civilisations come in contact and mix, causing all this contradictoriness in our nature, which no one can understand and which I call the baroqueness of mind. This is like a permanent intertwining of strong emotions, love, passion, tenderness, hatred, fear, sex and shame. The Balkans is a bridge between East and West, and this bridge is constantly swept by winds, which is why its history is so stormy. I do not think that my work can offer any answers, nor is there a rational interpretation or solution to the contradictoriness we refer to.

DD: The process of physical and mental preparation for the performance or a work of art has an important role in your work, and you call it "house cleaning". Can you tell us more about this analogy and understanding of the body as a house and, in general, about the practice of body “preparation”?

MA: From the mid-nineties, I have started workshops developing the idea of body preparation, alone and with my students. These workshops implied staying in a completely isolated place, as well as a special regime of life and mental and physical activities (seven days without communications, food, early morning rises, meditative exercises, etc.). After that, each of us would perform a task using only our own bodies. The term “house cleaning” is of recent origin because I really understand my body as a house, as do other artists - according to what they show in their works (e.g. Louise Bourgeois) - or other cultures (e.g. Muslim drawings). I think that what we should do now is clean the house. This house cleaning actually brings the body into a state that makes it especially receptive to a specific energy, and this state of “clear mind” makes it possible to create a work that will be sufficiently strong to transform others. If the artist does not have a clear mental picture, his/her work will express that state of disorder and inarticulateness. In the modern world, so deeply in crisis due to hyperproduction, art is not needed, as it only deepens the crisis and pollution. Art should be the oxygen of society.

“House cleanings” are the workshops I do with my students, but they are also my own performances. It is important, however, that body preparation is not practised only during specific periods but becomes a principle of life. I was influenced by a text of Cennino Cennini who writes how an artist should prepare himself to create a work of art when he is given an order from the pope or the king: he should stop eating meat three months before, drinking wine three months before, stop having sexual intercourse a month before, and three weeks before he should put a plaster on his right hand and then, when he is supposed to start painting, he will break the plaster and be able to draw a perfect circle. My concept of “Cleaning the House” follows in this tradition.

At the moment when all philosophical systems are brought into question, when the religious ones have lost their absoluteness, and the systems of values have disappeared, while the new ones are yet to come, the question of the role of the arts arises, along with the task of the artist.

Marina believes that an artist can be a companion who accompanies a person on a journey to discover his/her inner being. She creates art that goes beyond the level of visual perception and precisely opens new channels for awareness. In this sense, her work is interactive in a specific way, positioning the observer as the activating factor.

Interactivity becomes an increasingly dominant characteristic of modern art, regardless of the material the work is made of, since it corresponds to the principles of contemporary information systems, which fully shape our consciousness and behaviour.

Modern society is characterised by a frenetic need to overcome one's own limits of the body and consciousness, for the alternation of perception and communication, which are possible to realise through instant means of techno-culture.

In this context, the work of Marina Abramović is significant, as it does not express the romantic, utopian conviction that art can change the world, but rather instigates the real possibility of opening the channels of individual awareness of the world and its beings.

The interview is published in the catalogue of the exhibition “Performing Body”, edited by Charta, Milan.

studio Stefania Miscetti, Marina Abramović, Performing Body

INSTAGRAM

@EXPERIMENTS.FASHION.ART