2025

2011

JUDITH CLARK: TEACHING CURATING FASHION IS BECOMING EASIER

“Forms Becoming Attitudes”

Conversations on Fashion Curating for the CURA Magazine

2009 - 2012

Ilaria Marotta, founding director of CURA magazine, was my collaborator at MACRO - Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome. In 2008, after we were all forced to leave the museum due to the change of the Mayor of Rome and consequently the museum’s new direction, Ilaria started a free-press magazine in 2009, for which she asked me to collaborate.

My column was called “Forms Becoming Attitudes” and in every issue I was contributing with texts or interviews to curators dealing with fashion display in museums and other platforms.

This must have been one of the very pioneering surveys on Fashion Curating, still a very new field, since all I spoke with were known within a very niche of like-minded professionals.

I started with Linda Loppa, a founding director of MoMu in Antwerp and, back then, a newly appointed director of Polimoda in Florence. Then followed conversations with Tomas Rajnai, Maria Luisa Frisa, Helena Hertov, Judith Clark, Barbara Franchin, Sabine Seymour, Kaat Debo, Valerie Steele, Emanuele Quinz and Luca Marchetti.

Most of these names are today established and recognised fashion scholars, curators and exhibition makers.

Judith Clark is a professor of Fashion and Museology at the London College of Fashion, University of the Arts. She is one of the two co-founders of the Centre for Fashion Curation (CfFC) and is internationally recognised across academia, museums, galleries, industry and the press.

Exhibitions include “The Concise Dictionary of Dress” (with Adam Phillips) at Blythe House, London, commissioned by Artangel; “Diana Vreeland after Diana Vreeland” at Palazzo Fortuny, Venice, and “Chloe. Attitudes” (Palais de Tokyo, Paris 2012) which was updated in 2017 to “Chloé: Femininities” which involved creating a new archive exhibit at the new Maison Chloe in Paris. More recent exhibitions include “The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined”, curated for the Barbican Art Gallery in 2016, which travelled to the Winterpalais in Vienna and ModeMuseum, Hasselt (2017). In 2019 she curated and designed “Lanvin: Dialogues”, which celebrated 130 years of the Paris fashion house at the Fosun Foundation in Shanghai (the research will become a book published by La Martiniere in 2022); and in 2020, “Memos. On Fashion in This Millennium” with Maria Luisa Frisa at the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan.

In 2020, Clark opened a new studio in London J.Clark Space, in which to carry out and document practice-based research.

https://judithclarkstudio.com/

Dobrila Denegri: It would be interesting to begin our conversation by speaking about architecture… in particular about your formation as an architect and about your gradual transition towards the world of fashion… about, as Christopher Breward put it, potential parallels between “dressing the bodies” and “dressing the spaces”.

How did this shift occur in your case?

Judith Clark: I am not sure that such a shift ever happened, as I find it hard to see one without the other. I trained as an architect at the Bartlett School at UCL in London and then at the Architectural Association, where I was in the History and Theory Department rather than the design department. What was being discussed was not so much building design but the application of ideas and histories (abstract/conceptual) to the possibilities of a built environment (concrete). Always about what occurs between theory and practice. My research focused on Vsevolod Meyerhold, the great Russian theatre director, as a way of combining a previous love of dress/fashion/costume and utopian architecture: about what constructivist architects did with this dialogue for Meyerhold’s theatre in the 1920s.

DD: What were the challenges for you when the “Judith Clark Costume Gallery” set off? And what guided you in the choice of artists/designers to whom you dedicated exhibitions?

JC: Explicitly, each exhibition was dedicated to a different aspect of curating/theming dress. It was meant to be about the breadth of this discipline, so I had thought I would never repeat a theme. But I think we are, to a certain extent, bound to our own generation, so in retrospect, a lot of the people I collaborated with, though I often didn’t know them personally before collaborating with them, are about my age. Fundamentally, they were thinking about conceptual fashion at the same time I had been thinking about its representation off the catwalk and to some extent outside the museum walls. So people like Hussein Chalayan, Naomi Filmer, Simon Thorogood, Shelley Fox, Dai Rees, and Alexander McQueen. There is a discernible generational link. And I also curated historical shows which were about taking preoccupations that were more contemporary and tracing their genealogies backwards. The gallery was rooted in the present. I’m not sure I would approach it in the same way now – but it was a long time ago.

The challenges were financial, and the benefits were those challenges. We had to come up with ideas, and that was exhilarating. Moulding a support out of Perspex with a cigarette lighter – I did a lot of this kind of thing myself. I also didn’t know anyone in this field, and that was liberating as well. I wrote to people, not knowing what they were like other than that they might have written a book. I was creating what I hoped would be a dialogue around the gallery space, and it worked. I met some of my (now) best friends there.

DD: In your opinion, which have been the most significant exhibitions dedicated to fashion? Which are the moments that have placed fashion at the centre of a more serious reflection and have made it more culturally relevant?

JC: This is a difficult one, as there have actually been many that have been incrementally important – but I could also say there have been none.

DD: Is there a particular moment when you became aware that your work could be defined as “fashion curating”? Or, how would you define “curating” in relation to your own practice, and especially in relation to exhibitive formats you developed in collaboration with museums in Antwerp, London, and Rotterdam?

JC: My practice can be called fashion curating, I think, but my preferred title is one of exhibition-maker. Starting working on exhibitions within such a small gallery meant that I was designing and curating simultaneously, so when Linda Loppa commissioned my first larger show, “Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back” for ModeMuseum in Antwerp (that then became “Spectres” at the V&A) I was very clear that I wanted to design the exhibition structure as I went along: it had become integral to the curatorial process and it has stuck as a way of working. It is now absolutely central to my research. It is about what part of the narrative/history can be delegated to the mannequins and what aspect the dress itself carries. How are the connections made if not simply grouped on a plinth?

At the moment, I am preparing an exhibition at the University, and it is about Allegory, it is about The Judgement of Paris. It is about how do we know who the goddesses are without words as is the case within allegorical paintings? Who is Hera, who is Athena, and who is Aphrodite? And it is also about our ideas about beauty – and whether Paris decides. My preoccupations have been less about how to install a dress and more about what the vocabulary might be that we have at our disposal as curators of dress. Over and above spotlights, labels and plinths.

DD: Current dialogue between art, fashion and design is generating hybridisations requiring new classifications, a new lexicon, and a new manner of presentation within the structure of the exhibition. Fashion and design no longer seem so alien within the context of art. What is the importance of “the frame” in which fashion artefacts are placed, according to their intrinsic value and meaning? And what could the most suitable “frames” be? Could you imagine an “ideal exhibition space” for all the hybridisations of fashion and art being generated today?

JC: The frame is as important to me as the object, so it is a very good question. But I don’t believe that there is a hybridisation between the two, as I still see them as very distinct. I agree there is a category crisis, but I am not sure who is provoking it and in whose best interest it is. I think in a way your question is the interesting bit – and that is whether it is entirely to do with context?

DD: Among exhibitions recently curated / co-curated by you, one dealt more directly with “boundaries of fashion” and its way of dialoguing with art. Could you tell me more about the exhibition “The Art of Fashion: Installing Allusions” held in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen and about the premises on which you have been working?

JC: The exhibition was about formal allusions, associations between disparate objects. I kept the installation design intentionally very minimal so that the objects could resonate within the incredible gallery at Boijmans - the one that Harald Szeeman used in “A-historical Sounds” that the exhibition itself alluded to, as well as some very different references to Frederick Keisler's idea of galaxies. The point of the exhibition was to let objects resonate with others that had been produced under different conditions. I think it was misunderstood as about a more intentional attempt to draw attention to the conceptual aspects of dress, which were secondary to me. It raised very conflicting feelings about promoting this relationship at all, and when the Louise Bourgeois crates arrived, I was very tempted to send them back, to say, No, they do not belong here. I can't do it. I can't put them next to a hat. I could read the anxiety on the courier's face from her gallery, and I felt the same.

DD: You have been working on the “history of fashion curating” for quite some time… could you tell me more about the results of this research and the perspectives that it will try to open?

JC: I am working with Amy de la Haye, with whom I have worked closely at the London College of Fashion, on a book for Yale University Press. We are concentrating mainly on curating in the UK, though with some forays abroad, looking very closely at Beaton’s 1971 exhibition at the V&A as a seminal moment in the re-description of this discipline.

DD: You have been teaching at the FDA – IUAV for a few years, so I would like to ask about your courses and about the perspectives of “fashion curating” for the upcoming generations.

JC: Teaching curating fashion is becoming easier just by virtue of the fact that there have been more examples in different contexts that one can point to. There have now been enough conceptual catwalk shows, historic shows in museums, events, and performance art, such that the language/frame of reference is very broad.

The Director of the school is Maria Luisa Frisa, herself an inspiring and pioneering curator who has been so instrumental in transforming this language in Italy, so even if the students have only seen her work, then it is a great start. What I do is present curating to them as a series of questions that they might ask of their own collections, as though to describe their own work. It is a good way in. I get them to create a historical genealogy from their 'mood board'. So I work with their existing passions. I show them how to show the evolution of a design in their sketchbook, where the dresses might be placed in a room and a narrative, or a themed preoccupation might emerge. They then build a scale model of a hypothetical museum space. It is wonderful when it works.

Published in cura.artmagazine issue 07

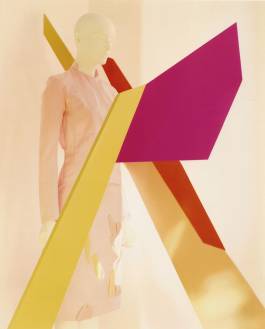

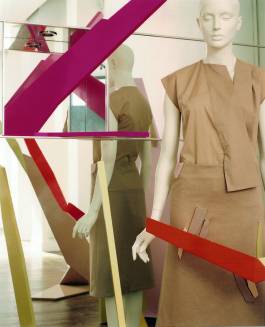

Simon Thorogood, “Fascia”, Judith Clark Costume Gallery, London, 2000.

Simon Thorogood, “Fascia”, Judith Clark Costume Gallery, London, 2000.

Simon Thorogood, “Fascia”, Judith Clark Costume Gallery, London, 2000.

Simon Thorogood, “Fascia”, Judith Clark Costume Gallery, London, 2000.

A complete 'family' of 9 “Fascia” constructions were shown alongside two garments from his S/S 2001 collection. “Fascia” was a capsule collection of garments and constructions partly designed through chance processes in which various sections and edits of aircraft were combined and fused together to create new forms and structures.

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

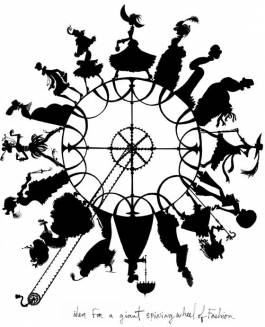

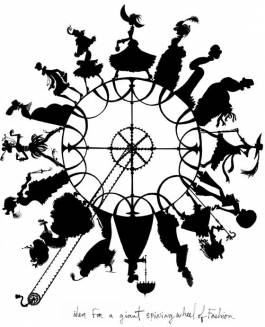

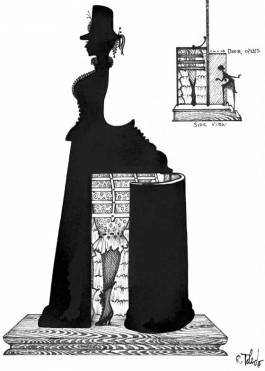

Ruben Toldeo, “Idea for a giant spinning wheel of fashion”, 2003.

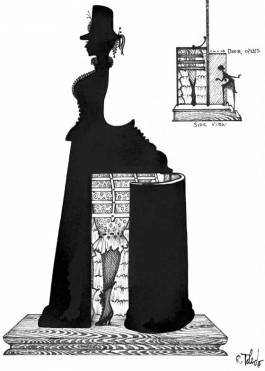

Ruben Toledo, “Take a peek at this crinoline”, 2004.

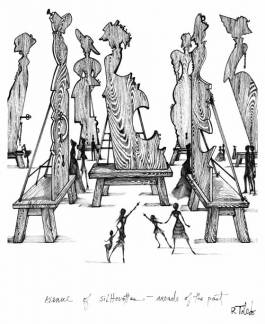

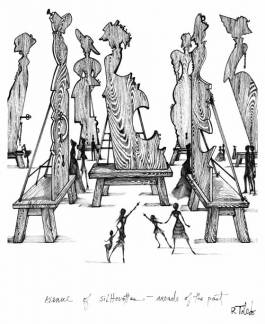

Ruben Toledo, “Avenue of Silhouettes”, 2003.

Details of the “Avenue of Silhouettes”, "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

Photography by Ronald Stoops

“The Magic Lantern” for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“The Magic Lantern” for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“The Magic Lantern” for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Labyrinth” for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Locking in and Out”, cogs with dresses for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Marionette Theatre”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Curiosity Cabinet”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Merry-go-round”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Merry-go-round”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Remixing It - The Past In Pieces”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Remixing It - The Past In Pieces”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

The exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

The exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

Veronique Branquinho, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

2025

“Forms Becoming Attitudes”

Conversations on Fashion Curating for the CURA Magazine

2009 - 2012

Ilaria Marotta, founding director of CURA magazine, was my collaborator at MACRO - Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome. In 2008, after we were all forced to leave the museum due to the change of the Mayor of Rome and consequently the museum’s new direction, Ilaria started a free-press magazine in 2009, for which she asked me to collaborate.

My column was called “Forms Becoming Attitudes” and in every issue I was contributing with texts or interviews to curators dealing with fashion display in museums and other platforms.

This must have been one of the very pioneering surveys on Fashion Curating, still a very new field, since all I spoke with were known within a very niche of like-minded professionals.

I started with Linda Loppa, a founding director of MoMu in Antwerp and, back then, a newly appointed director of Polimoda in Florence. Then followed conversations with Tomas Rajnai, Maria Luisa Frisa, Helena Hertov, Judith Clark, Barbara Franchin, Sabine Seymour, Kaat Debo, Valerie Steele, Emanuele Quinz and Luca Marchetti.

Most of these names are today established and recognised fashion scholars, curators and exhibition makers.

Judith Clark is a professor of Fashion and Museology at the London College of Fashion, University of the Arts. She is one of the two co-founders of the Centre for Fashion Curation (CfFC) and is internationally recognised across academia, museums, galleries, industry and the press.

Exhibitions include “The Concise Dictionary of Dress” (with Adam Phillips) at Blythe House, London, commissioned by Artangel; “Diana Vreeland after Diana Vreeland” at Palazzo Fortuny, Venice, and “Chloe. Attitudes” (Palais de Tokyo, Paris 2012) which was updated in 2017 to “Chloé: Femininities” which involved creating a new archive exhibit at the new Maison Chloe in Paris. More recent exhibitions include “The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined”, curated for the Barbican Art Gallery in 2016, which travelled to the Winterpalais in Vienna and ModeMuseum, Hasselt (2017). In 2019 she curated and designed “Lanvin: Dialogues”, which celebrated 130 years of the Paris fashion house at the Fosun Foundation in Shanghai (the research will become a book published by La Martiniere in 2022); and in 2020, “Memos. On Fashion in This Millennium” with Maria Luisa Frisa at the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan.

In 2020, Clark opened a new studio in London J.Clark Space, in which to carry out and document practice-based research.

https://judithclarkstudio.com/

2011

JUDITH CLARK: TEACHING CURATING FASHION IS BECOMING EASIER

Dobrila Denegri: It would be interesting to begin our conversation by speaking about architecture… in particular about your formation as an architect and about your gradual transition towards the world of fashion… about, as Christopher Breward put it, potential parallels between “dressing the bodies” and “dressing the spaces”.

How did this shift occur in your case?

Judith Clark: I am not sure that such a shift ever happened, as I find it hard to see one without the other. I trained as an architect at the Bartlett School at UCL in London and then at the Architectural Association, where I was in the History and Theory Department rather than the design department. What was being discussed was not so much building design but the application of ideas and histories (abstract/conceptual) to the possibilities of a built environment (concrete). Always about what occurs between theory and practice. My research focused on Vsevolod Meyerhold, the great Russian theatre director, as a way of combining a previous love of dress/fashion/costume and utopian architecture: about what constructivist architects did with this dialogue for Meyerhold’s theatre in the 1920s.

DD: What were the challenges for you when the “Judith Clark Costume Gallery” set off? And what guided you in the choice of artists/designers to whom you dedicated exhibitions?

JC: Explicitly, each exhibition was dedicated to a different aspect of curating/theming dress. It was meant to be about the breadth of this discipline, so I had thought I would never repeat a theme. But I think we are, to a certain extent, bound to our own generation, so in retrospect, a lot of the people I collaborated with, though I often didn’t know them personally before collaborating with them, are about my age. Fundamentally, they were thinking about conceptual fashion at the same time I had been thinking about its representation off the catwalk and to some extent outside the museum walls. So people like Hussein Chalayan, Naomi Filmer, Simon Thorogood, Shelley Fox, Dai Rees, and Alexander McQueen. There is a discernible generational link. And I also curated historical shows which were about taking preoccupations that were more contemporary and tracing their genealogies backwards. The gallery was rooted in the present. I’m not sure I would approach it in the same way now – but it was a long time ago.

The challenges were financial, and the benefits were those challenges. We had to come up with ideas, and that was exhilarating. Moulding a support out of Perspex with a cigarette lighter – I did a lot of this kind of thing myself. I also didn’t know anyone in this field, and that was liberating as well. I wrote to people, not knowing what they were like other than that they might have written a book. I was creating what I hoped would be a dialogue around the gallery space, and it worked. I met some of my (now) best friends there.

DD: In your opinion, which have been the most significant exhibitions dedicated to fashion? Which are the moments that have placed fashion at the centre of a more serious reflection and have made it more culturally relevant?

JC: This is a difficult one, as there have actually been many that have been incrementally important – but I could also say there have been none.

DD: Is there a particular moment when you became aware that your work could be defined as “fashion curating”? Or, how would you define “curating” in relation to your own practice, and especially in relation to exhibitive formats you developed in collaboration with museums in Antwerp, London, and Rotterdam?

JC: My practice can be called fashion curating, I think, but my preferred title is one of exhibition-maker. Starting working on exhibitions within such a small gallery meant that I was designing and curating simultaneously, so when Linda Loppa commissioned my first larger show, “Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back” for ModeMuseum in Antwerp (that then became “Spectres” at the V&A) I was very clear that I wanted to design the exhibition structure as I went along: it had become integral to the curatorial process and it has stuck as a way of working. It is now absolutely central to my research. It is about what part of the narrative/history can be delegated to the mannequins and what aspect the dress itself carries. How are the connections made if not simply grouped on a plinth?

At the moment, I am preparing an exhibition at the University, and it is about Allegory, it is about The Judgement of Paris. It is about how do we know who the goddesses are without words as is the case within allegorical paintings? Who is Hera, who is Athena, and who is Aphrodite? And it is also about our ideas about beauty – and whether Paris decides. My preoccupations have been less about how to install a dress and more about what the vocabulary might be that we have at our disposal as curators of dress. Over and above spotlights, labels and plinths.

DD: Current dialogue between art, fashion and design is generating hybridisations requiring new classifications, a new lexicon, and a new manner of presentation within the structure of the exhibition. Fashion and design no longer seem so alien within the context of art. What is the importance of “the frame” in which fashion artefacts are placed, according to their intrinsic value and meaning? And what could the most suitable “frames” be? Could you imagine an “ideal exhibition space” for all the hybridisations of fashion and art being generated today?

JC: The frame is as important to me as the object, so it is a very good question. But I don’t believe that there is a hybridisation between the two, as I still see them as very distinct. I agree there is a category crisis, but I am not sure who is provoking it and in whose best interest it is. I think in a way your question is the interesting bit – and that is whether it is entirely to do with context?

DD: Among exhibitions recently curated / co-curated by you, one dealt more directly with “boundaries of fashion” and its way of dialoguing with art. Could you tell me more about the exhibition “The Art of Fashion: Installing Allusions” held in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen and about the premises on which you have been working?

JC: The exhibition was about formal allusions, associations between disparate objects. I kept the installation design intentionally very minimal so that the objects could resonate within the incredible gallery at Boijmans - the one that Harald Szeeman used in “A-historical Sounds” that the exhibition itself alluded to, as well as some very different references to Frederick Keisler's idea of galaxies. The point of the exhibition was to let objects resonate with others that had been produced under different conditions. I think it was misunderstood as about a more intentional attempt to draw attention to the conceptual aspects of dress, which were secondary to me. It raised very conflicting feelings about promoting this relationship at all, and when the Louise Bourgeois crates arrived, I was very tempted to send them back, to say, No, they do not belong here. I can't do it. I can't put them next to a hat. I could read the anxiety on the courier's face from her gallery, and I felt the same.

DD: You have been working on the “history of fashion curating” for quite some time… could you tell me more about the results of this research and the perspectives that it will try to open?

JC: I am working with Amy de la Haye, with whom I have worked closely at the London College of Fashion, on a book for Yale University Press. We are concentrating mainly on curating in the UK, though with some forays abroad, looking very closely at Beaton’s 1971 exhibition at the V&A as a seminal moment in the re-description of this discipline.

DD: You have been teaching at the FDA – IUAV for a few years, so I would like to ask about your courses and about the perspectives of “fashion curating” for the upcoming generations.

JC: Teaching curating fashion is becoming easier just by virtue of the fact that there have been more examples in different contexts that one can point to. There have now been enough conceptual catwalk shows, historic shows in museums, events, and performance art, such that the language/frame of reference is very broad.

The Director of the school is Maria Luisa Frisa, herself an inspiring and pioneering curator who has been so instrumental in transforming this language in Italy, so even if the students have only seen her work, then it is a great start. What I do is present curating to them as a series of questions that they might ask of their own collections, as though to describe their own work. It is a good way in. I get them to create a historical genealogy from their 'mood board'. So I work with their existing passions. I show them how to show the evolution of a design in their sketchbook, where the dresses might be placed in a room and a narrative, or a themed preoccupation might emerge. They then build a scale model of a hypothetical museum space. It is wonderful when it works.

Published in cura.artmagazine issue 07

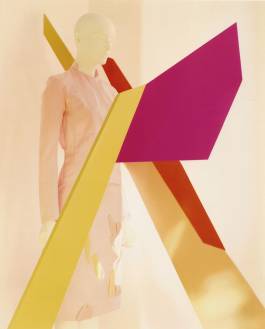

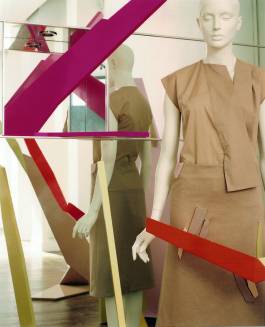

Simon Thorogood, “Fascia”, Judith Clark Costume Gallery, London, 2000.

Simon Thorogood, “Fascia”, Judith Clark Costume Gallery, London, 2000.

Simon Thorogood, “Fascia”, Judith Clark Costume Gallery, London, 2000.

Simon Thorogood, “Fascia”, Judith Clark Costume Gallery, London, 2000.

A complete 'family' of 9 “Fascia” constructions were shown alongside two garments from his S/S 2001 collection. “Fascia” was a capsule collection of garments and constructions partly designed through chance processes in which various sections and edits of aircraft were combined and fused together to create new forms and structures.

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Malign Muses: When Fashion Turns Back

Mode Museum, Antwerp

(c) Photography: Ronald Stoops

Ruben Toldeo, “Idea for a giant spinning wheel of fashion”, 2003.

Ruben Toledo, “Take a peek at this crinoline”, 2004.

Ruben Toledo, “Avenue of Silhouettes”, 2003.

Details of the “Avenue of Silhouettes”, "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

Photography by Ronald Stoops

“The Magic Lantern” for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“The Magic Lantern” for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“The Magic Lantern” for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Labyrinth” for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Locking in and Out”, cogs with dresses for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Marionette Theatre”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Curiosity Cabinet”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Merry-go-round”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Merry-go-round”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Remixing It - The Past In Pieces”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

“Remixing It - The Past In Pieces”, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

The exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

The exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

Veronique Branquinho, for the exhibition "Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back" (24 February - 8 May 2005), Victoria and Albert Museum, copyright V&A.

INSTAGRAM

@EXPERIMENTS.FASHION.ART