ELISE BY OLSEN: FOCUS WAS ON THE IMMATERIAL PRODUCTION OF FASHION, RATHER THAN DESIGN, TEXTILES, OR CLOTHING

In this interview, editor and founding director of the International Library of Fashion Research, Elise By Olsen, speaks with fashion researcher and ILFR alumni Carolina Davalli about the evolution of her publishing practice and the foundational ideas behind ILFR. The conversation traces the origins of Wallet, a fashion criticism publication launched in 2018, and how its editorial vision laid the groundwork for the creation of the Library. Through reflections on collaboration, archiving, digital access, and the overlooked cultural value of fashion ephemera, Olsen articulates a vision of fashion research that is open, interdisciplinary, and materially engaged. The dialogue offers insight into the challenges and ambitions of building an institution dedicated to the preservation and public accessibility of printed fashion matter, while also highlighting the playful, critical, and community-driven ethos that defines her practice and ILFR’s ethos.

Carolina Davalli: I’d like to begin by discussing the story of Wallet, a fashion commentary publication you founded in 2018. How did this publication come into being?

Elise By Olsen: I started Wallet as a fashion criticism publication together with curator, historian, and cultural critic Jeppe Ugelvig; Geir Haraldseth, curator of contemporary art at the National Museum of Norway; and Creative Director and current Design Director of ILFR Morteza Vaseghi. In 2018, I felt a growing sense of frustration with the fashion industry, and I kept it at arm's length while engaging in other publishing projects. I was never fully part of the fashion industry–it was always a one-foot-in, one-foot-out situation. Still, there were many influential figures I found highly intimidating, and there was an anti-authoritarian impulse in me that wanted to confront them, to sit them down and ask them questions.

With Wallet, we addressed 10 issues, leading to significant institutional criticism across various fields. Our focus was on the immaterial production of fashion, rather than design, textiles, or clothing. The first issue, titled Admins of Authority, centred on power, money, and politics in fashion. The second issue explored fashion publishing. We also produced an issue on fashion education and discursive spaces, which included a conversation with Matthew Linde, along with many other esteemed colleagues. Additionally, we addressed themes such as retail spaces, casting, marketing, and technology. The final issue we released was Issue 10, titled Heirs of History, which focused on archiving and archival practices in fashion.

CD: That last issue served as a precursor to broader reflections on archives, libraries, and fashion documents’ collections. By 2021, this line of inquiry had fully emerged, and the library was already in development. I’d also like to highlight a particular design feature of Wallet: the tearable advertisements. This element underscores the often-unspoken rule in fashion magazines and publications that advertisements are a necessary inclusion. In this context, the design becomes a metaphor for that very notion. What I particularly appreciate is the sense of playfulness it introduces. So, I’d like to ask: what role does playfulness play in your practice?

EBO: Humour is essential, and criticism can be both enjoyable and executed in many inventive ways. Again, the position of partial involvement in the industry enabled us to explore and implement features like these. Morteza and I had previously worked on a youth culture magazine called Recens Paper that I founded five years before launching Wallet. In that instance, we sold advertisements to keep the magazine in circulation, and, while we needed the ads to sustain the publication, we also had a very young readership and therefore we felt a responsibility to make it clear that these were paid placements.

To do this, we implemented a two-and-a-half-centimetre advertisement warning border, which was featured in the magazine. Within that border, we placed ads paid for by brands such as Gucci, Prada, and Mercedes-Benz. Importantly, we always sold the ad space with the understanding that the specifications applied only within that clearly marked border. In theory, this left little room for objection. Still, we did have one advertiser who was quite upset, but our justification was always: “This is what young people want.” And, somehow, we got away with it.

As a young person in this industry, I’ve been able to be more frank, irreverent, and playful–perhaps even naive, sometimes. This approach to advertising marked a second iteration of that same spirit. In Wallet, we introduced perforated advertisements, meaning that the pages dedicated to the ads featured a perforation finishing down the side so that they could be torn out of the magazine. Some advertisers again expressed frustration, but we explained: “The perforation is there so readers can tear out the ad and put it up as a poster.” And we got away with that, too.

CD: Wallet served as a stepping stone for the International Library of Fashion Research. In what ways did it lead to the foundation of the library?

EBO: Well, it began with the fact that I consider myself a publisher first and foremost, and fashion has served as a kind of thematic filter, a way to shape and guide my output. Without this deep enthusiasm for print, I wouldn’t have founded a fashion research library with such an emphasis on printed and material culture. Becoming an archivist, however, was a serendipitous turn. While working on various issues of Wallet, particularly the issue on fashion criticism, we interviewed an anonymous fashion critic named Steve Oklyn. He ran a blog called Not Vogue, where he published guerrilla-style, fiercely critical pieces. He even maintained a blacklist that featured many of the most influential figures in the fashion industry. Indiscriminately anti-establishment. He attracted significant attention, though no one knew his identity.

Eventually, through our interview, he revealed himself to be a reclusive 70-year-old man living in New York, named Steven Mark Klein. He had been collecting printed fashion materials from 1975 to the present. He became an unexpected mentor to me — not someone I had sought, but he declared, “I’m going to be your mentor,” and proceeded to share a wealth of knowledge and research materials. He would call me daily from his landline in New York — he didn’t own a smartphone — and over time, we developed a deep intellectual connection.

One day, he asked me if I would like to inherit his collection, which consisted of approximately 5.000 objects, along with a substantial amount of branded ephemera. He wasn’t wealthy; he built the collection by visiting store counters in downtown New York and luxury boutiques, collecting catalogues, business cards, and press releases–materials he acquired for free. What began as a personal archive grew into something massive and culturally significant. But his intention was never to publicise the collection or make it accessible; it was a private pursuit. Interestingly, before amassing this fashion archive, Klein collected art books. This transition from collecting art books to fashion materials underscores the intersection between fashion and art, and how one form of cultural collecting can evolve into another.

A particularly meaningful example from his archive is the Matsuda 1996 catalogue, which features the Naked New York photographic series – it’s one of the most personal objects in the collection. There’s a beautiful quote from Steven that marks the profound connection between fashion and art — one that continues to shape our work at the library.

“I got these copies, which are now part of the ILFR collection, at an opening at Matthew Marks gallery in 1996, where Nan’s photos for Naked New York were exhibited. There was a pile of these books on the floor of the gallery, and not to be greedy, I only took two. People honestly should have taken like 30. The title photographer is not enough for Nan Goldin, she truly is an artist.” - SMK

CD: What was it about fashion printed matter that struck him the most?

EBO: He recognised the significance and research value of branded fashion materials, considering them just as important as the art books he had previously collected. He studied at the School of Visual Arts alongside the painter Julian Schnabel. For a period, he even lived in Jean-Michel Basquiat’s loft in New York and was part of that vibrant scene in the early 1970s. He was a passionate book collector and initially began by gathering artist books from his circle of friends. He also amassed press releases from various exhibitions in which his friends were featured.

Over time, these materials became incredibly rare and valuable — so much so that he eventually sold many of them to pay his rent in New York. He was married to a ballet dancer, Molissa Fenley, who was a muse for Robert Mapplethorpe and walked in some of the shows staged by fashion conglomerates in Paris in the early 1980s. Stephen accompanied her on one of those trips and attended a show where he came across a pamphlet for a fashion brand. It featured the best photographers, commissioned artists, stylists, copywriters, and so on. That’s when he decided that was what he wanted to collect next.

There’s another quote from Steven, which makes me think about the power of sourcing and accessing information.

“Fashion knowledge operates on the same intellectual level as scientific knowledge. Both are about discovery, paradigm shifts, and revolution.” - SMK

CD: That leads me to wonder: when did you decide to open the International Library of Fashion Research? Was the idea of free access always part of your vision, or did that come later?

EBO: Yes, access is the foundation of this project. When I was asked to inherit the collection, my immediate thought was: “I don’t have the domestic space to store 5,000 objects–not in my dad’s garage, not anywhere.” I simply lacked the space. But there was also a deeper responsibility. Steven had asked me not only to preserve the collection but to continue building it and carrying it forward. Around the same time, I reached out to the National Museum of Norway and asked if they had the space to host the collection. That’s how the transition happened: the collection moved from New York to Oslo.

I didn’t fully grasp the scale of the project until two tons of printed matter arrived in a shipping container at the Oslo harbour. At that moment, I thought: “What have I done? There’s no turning back.” After the collection arrived in Norway, however, things paused for a while. The library’s first visual and public manifestations emerged through its digital presence, primarily via Instagram and the website. These platforms became the first means of sharing the library’s network, programming, and events. The website, in particular, functions as a space for displaying selected objects from the collection, offering digital access to the materials.

CD: Since these digital platforms were the project’s first outward-facing expressions, I’d like to discuss more about the role of digital media within the library. I also think it’s significant that this collection was brought to Oslo specifically and has since become a coveted and institutionalised resource.

EBO: Oslo is an off-the-grid city, which makes it a unique and intentional location for housing this collection. At the same time, it offers a kind of neutrality to our work. The city offers a meditative and reflective space – the fashion scene here is relatively small. Although Oslo hosts a modest fashion week, many designers and brands educated or based in the city eventually move abroad due to the lack of a developed industry or broader ecosystem. For us, placing the physical library off the grid was important–it emphasised the need for a robust digital platform where anyone, anywhere, could access and understand the scope of the collection, the types of materials we house, and the contributions made by others.

After the library’s physical opening in Oslo in November 2022, we’ve established a meaningful connection between digital and physical research. We don’t hold the rights to fully digitise every publication, and attempting to do so would not only be an enormous undertaking but would also contradict our commitment to keeping the library open, free of paywalls, and accessible without requiring a login. At https://fashionresearchlibrary.com, you can explore our holdings freely: you can browse items and their metadata, submit research requests, and even build your own digital ‘stacks’ of materials. From there, you can schedule an appointment to visit us in person and consult the physical collection.

We also welcome walk-ins during our public opening hours. This is not merely an archive, it’s a working library designed to be used and accessed. The digital dimension is equally critical: we offer curated digital experiences, or micro-curations, where contributors and guest-researchers select groups of materials to offer thematic perspectives on particular topics.

CD: Every curatorial intervention in the physical library is supported by a digital showcase of the featured objects. These pathways are designed to be intuitive–each object leads to another, and the metadata embedded in the database creates a parallel research journey. It’s a simple but powerful way to navigate the collection and connect with materials through both thematic and serendipitous associations.

EBO: When we first secured funding to build the website and launch the digital institution, we asked ourselves: “What kind of digital spaces currently exist within fashion?” Unsurprisingly, the e-commerce website emerged as the dominant and most recognisable model. As a result, our website borrows heavily from the visual and structural language of e-commerce.

It’s difficult to describe in a single sentence, but essentially, each object is treated with the same level of attention you might expect in a luxury retail interface. For instance, beneath each item, you’ll find suggestions like “You might also like,” “More from this designer,” or “More silver printed objects.” These features help to create associative pathways through the collection.

This duality is intentional: we want researchers who come with a specific focus to be able to locate what they need quickly and efficiently. At the same time, we want to encourage browsing and discovery. It’s about creating a space where structured research and serendipitous exploration can coexist, whether you arrive with a question or just curiosity.

CD: The collection primarily consists of printed matter and ephemera related to fashion – materials that private collectors, institutional archives, or brand vaults have traditionally gate-kept. Making these materials freely accessible — without paywalls, credential requirements, or institutional mediation — was, at the time, truly groundbreaking.

EBO: We announced the digital database and started the library project in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the industry was at a complete standstill. There was no way to continue producing within the apparatus and machinery we were accustomed to. After the pandemic, the industry returned stronger to compensate for the brand's commercial losses. It was fascinating to see that we could no longer create eight collections a year or the 40 million campaigns on billboards and digital platforms when production halted.

In this scenario, the brands and fashion houses had to revisit their archives. Many realised they lacked adequate documentation of their histories. There had been little reflection on the past, and documentation of both tangible and intangible assets was insufficient. This situation underscores the critical significance of our project, as much of the material we hold comprises content that brands themselves do not possess.

You used the term “gate-kept,” which is crucial here: while collections and libraries of this nature certainly exist elsewhere, our collection is unique in its openness and accessibility. It is not a subordinate component of a costume collection, nor is it confined to a university or academic institution accessible only to select students and professors. This is an open resource, freely available to all.

Much of the material we hold — press releases, fashion show invitations, and other ephemera — historically circulated within very limited environments, restricted to the press, VIP customers, and buyers. Sharing these materials with the general public is therefore quite meaningful. Traditionally, fashion printed materials have been treated as ancillary to the presentation of fashion itself. Incorporating them into a curatorial project is a fascinating development because it celebrates these objects, which have long been under-researched.

CD: How is this collaborative approach reflected or embodied in the physical space of the library, as well as through its digital presence?

EBO: While the archive, library, and research resources are all vital components of ILFR, the library also functions as a meeting point, a communal and collaborative space for thinking, gathering, and exchange. The study area reflects this ethos. The library is not just a repository of the past, but a living space for dialogue and inquiry.

What’s particularly interesting about the creation of this space is its evolution from a digital platform into a physical environment. Vésma Kontere McQuillan, at the time our Head of Spatial Design of ILFR, took inspiration from the concept of metaspace and collaborated with her students from Kristiania University of Oslo to design the library’s interior. The idea of layered mediation — where the digital informs the physical and vice versa — is liberating and full of possibility. Vésma described the library project as an ideal laboratory to experiment with the spatial dynamics of fashion, which aligns closely with her academic focus and design practice.

The whole point is to create a space where, for example, a student–whether in graphic design, fashion design, or another related field–can encounter and engage with an industry expert, an architect, or a business executive from Norway or abroad. The library functions as a forum for discourse and dialogue, where meaningful interaction serves not only as a springboard for emerging local talent onto the international stage but also as a means of enriching and stimulating the local scene through a global network. This interconnectedness is absolutely vital to our mission.

CD: ILFR also hosts a physical exhibition space. What’s particularly interesting is that many of the props and materials in the space were donated.

EBO: Take, for example, the cardboard seats from Prada’s Spring/Summer 2023 show–yes, where Kim Kardashian and Anna Wintour sat. We managed to facilitate a donation from Prada, and since the seats were made from cardboard, they were a perfect fit for our collection, which focuses on printed and paper-based materials.

This donation also opened up new curatorial thinking about fashion show seating as ephemera and as physical artefacts that encapsulate the atmosphere of a particular moment in time. They reflect not just the audience, but the values, material choices, and staging of a given season. It’s an area we’re still exploring, but one that offers a fascinating intersection of utility, symbolism, and temporality in fashion history. We’re also in need of new auditorium seating, as we now host a growing number of talks, seminars, and workshops.

The goal is to create a modular seating system that doubles as storage, with compartments built into the units. Interestingly, the current benches came from an art exhibition at the Oslo Art Museum. They were about to be discarded, and (as often happens) we salvaged them before they ended up in the trash. This kind of resourceful repurposing reflects the broader ethos of the library.

CD: What is ILFR’s approach to cultural partnerships, and how does the acquisition process work?

EBO: We are committed to considering multiple perspectives and resisting exclusivity, especially in our partnerships. Our collection includes a wide range of brands–we deliberately avoid aligning ourselves with any single fashion house. Similarly, when we carry out educational projects, we collaborate with all types of institutions: public and private, large and small, including those that might be seen as competitors. As we know, the fashion education system is highly competitive, and this inclusive approach is a conscious departure from that norm. These are some of the core principles of the Library, and they also resonate strongly with the values of our many donors who help grow the Library.

One methodology we use to honour our donors is a form of micro-curation, in which we present curated selections–what we sometimes refer to as ‘greatest hits’–in a dedicated cabinet display. This showcases the diversity and richness of our donations and functions as a living archive of the library’s evolution.

This idea of dotting the life of the library with curatorial interventions is a compelling one. It allows us to narrate the story of the collection in fragments, through specific donations, moments, and collaborations. And truly, we are nothing without our donors. The library operates without an acquisitions budget. We are still piecing together the funding required to sustain the project, and we rely almost entirely on donations. Our collection strategy is therefore quite intentional and hands-on: if we identify a gap or an object we believe should be part of the collection, we reach out directly—we ask, we explain, and yes, we beg, hopefully, with charm.

And, thankfully, people do respond. Larger fashion houses, publishers, and private collectors often offer materials freely and generously. But where we really feel the limitation is with emerging designers and independent practitioners who are working with printed matter as part of their creative processes. For them, contributing to the library can be financially burdensome. This is where a small acquisitions budget could make a real difference, allowing us to support and preserve new voices in fashion print culture.

CD: ILFR offers a very full program of cultural events, exhibitions, seminars, and workshops. Can you mention some of the most recent projects you worked on, organised or participated in?

EBO: A lot has happened in the library’s first year. We hosted many in-house exhibitions, two Fashion Research Symposiums in collaboration with the National Museum, a travelling exhibition, and an international residency and cultural intervention.

Queering Fashion was our first exhibition, and it marked a significant milestone as it also included commissioned artworks and became a travelling display. With this project, we explored the concept of site specificity within cultural institutions. As an international library, we’re not fixed to one place. We can move, adapt, and create temporary or travelling library structures, extending our reach while engaging new publics. These exhibitions also serve as a valuable tool for identifying and addressing gaps in our collection, expanding it through curated inquiry.

Expanding beyond the physical limits of the library, we also launched an exciting collaborative project with the Palais Galliera. This served as both an archival and an educational exchange, an initiative we aim to pursue further.

That collaboration became a stepping stone toward yet another intervention, this time involving the library’s presence within the spaces and collections of Atopos CVC in Athens. Atopos holds an extraordinary archive of paper-based garments and ephemera. Else and I went to Athens for a month, with the aim of working directly with Atopos' archive and collection. Initially, we weren’t planning to create an exhibition. However, as we immersed ourselves in the work, certain thematic threads emerged and the exhibition came to life.

Finally, I’d like to mention the exhibition Ephemeral Matters. Into the Fashion Archive, guest-curated by Marco Pecorari, Ph.D. in Fashion Studies and Director of the MA programme in Fashion Studies at Parsons School of Design, Paris, in collaboration with curator at the National Museum Hanne Eide. In the exhibition, ILFR was present as one of the six different partner institutions showcasing their collections of fashion ephemera.

CD: To conclude, I’d like to highlight the team at ILFR, which is highly interdisciplinary, bringing together individuals with diverse areas of expertise and backgrounds. This appears to reflect a core aspect of your broader practice – opening up dialogue across disciplines and challenging traditional hierarchies between them. The team includes members of the Board, the core staff, and a rotating group of guest researchers and interns, all of whom contribute meaningfully to the development and direction of the project. Could you tell us a bit more about how this collaborative structure works?

EBO: I previously mentioned Morteza and Vèsma, and then there is Else Skålvoll Thorenfeldt, our Head of Communications at ILFR. Else worked with Martin Margiela in the late 1980s and 1990s, when paper was still one of the most vital mediums in fashion communication. She has a remarkable sensitivity to materiality, and her reflections on touch and physical interaction with printed matter are central to her approach. Researcher Ilaria Trame has been the first Head Librarian of ILFR, and continues to collaborate with the project. We also have a circulation of students and guest researchers who come to work at the Library and conduct both physical and theoretical research. Since the physical opening in November 2022, we have had 15 researchers. This is a big part of the Library as a platform and meeting point. So, we have a core team, and many people who orbit around and interact with the Library.

We also have an extensive advisory board that, now that the physical library is open, can be more actively involved. Their guidance will help shape the direction of the collection’s growth. Since the collection first arrived in Oslo, its size has tripled to approximately 15,000 objects.

It’s a process of continuous renewal — a consistent updating and circulation of people engaging with the material in different ways. As we often say, this archive is nothing without the bodies it touches. It’s the people — through oral histories, memories, research, and interdisciplinary perspectives — who activate and bring meaning to the objects. The materials aren’t static; they come alive through interaction.

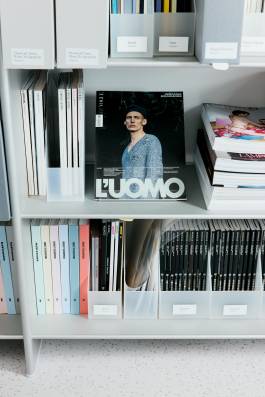

International Library of Fashion Research

Photograph by Magnus Gulliksen

INSTAGRAM

@EXPERIMENTS.FASHION.ART